not ezra

not ezrawhy is it always cis white dudes talking about how "identity politics" detract from class discourse? do they not have enough brain elasticity to think about the intersections of class, race and gender at the same time or something? jfc

Intersections of class, gender and race =/= identity politics. Have you guys ever read Crenshaw? This is her main idea when it comes to intersectionality

@Nightmares do u have any reading on the distinction between identity politics and representation politics

stingray

stingrayIntersections of class, gender and race =/= identity politics. Have you guys ever read Crenshaw? This is her main idea when it comes to intersectionality

I haven't pls link

Scratchin Mamba

Scratchin Mamba@Nightmares do u have any reading on the distinction between identity politics and representation politics

The CRC identified their recognition of this political tension as “identity politics.” The CRC statement is believed to be the first text where the term “identity politics” is used. Since 1977, that term has been used, abused, and reconfigured into something foreign to its creators. The CRC made two key observations in their use of “identity politics.” The first was that oppression on the basis of identity—whether it was racial, gender, class, or sexual orientation identity—was a source of political radicalization. Black women were not radicalizing over abstract issues of doctrine; they were radicalizing because of the ways that their multiple identities opened them up to overlapping oppression and exploitation. Black women’s social positions made them disproportionately susceptible to the ravages of capitalism, including poverty, illness, violence, sexual assault, and inadequate healthcare and housing, to name only the most obvious. These vulnerabilities also made Black women more skeptical of the political status quo and, in many cases, of capitalism itself. In other words, Black women’s oppression made them more open to the possibilities of radical politics and activism.

The Marxist tradition had also recognized this dynamic when Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin identified the “special oppression” of national minorities as an added burden they faced. Lenin used this framework of “special oppression” to call upon the Communist Party in the 1920s to become more active in the struggles of Black people against racism.** Lenin also recognized that the layers of oppression (1/~)

faced by Black people made them, potentially, more curious about and open to the arguments of the Communists.

But “identity politics” was not just about who you were; it was also about what you could do to confront the oppression you were facing. Or, as Black women had argued within the broader feminist movement: “the personal is political.” This slogan was not just about “lifestyle” issues, as it came to be popularly understood, rather it was initially about how the experiences within the lives of Black women shaped their political outlook. The experiences of oppression, humiliations, and the indignities created by poverty, racism, and sexism opened Black women up to the possibility of radical and revolutionary politics. This is, perhaps, why Black feminists identified reproductive justice as a priority, from abortion rights to ending the sterilization practices that were common in gynecological medicine when it came to treating working-class Black and Puerto Rican women in the United States, including Puerto Rico. Identity politics became a way that those suffering that oppression could become politically active to confront it. This meant taking up political campaigns not just to ensure the liberation of other people but also to guarantee your own freedom. It was also of critical importance that the CRC statement identified “class oppression” as central to the experience of Black women, as in doing so they helped to distinguish radical Black feminist politics from a developing middle-class orientation in Black politics that was on the ascent in the 1970s. Indeed, the intersecting factors of race, gender, and class meant that Black women were overrepresented in the ranks of the poor and working class. (2/~)

Combahee’s grasp of the centrality of class in Black women’s lives was not only based in history but was also in anticipation of its growing potential as a key divide even among Black women. Today that could not be clearer. The number of Black women who are wealthy and elite is small, but they are extremely visible and influential. From Michelle Obama to Oprah Winfrey to US senator Kamala Harris, they, as so many other Black wealthy and influential people, are held up as examples of American capitalism as just and democratic. They are represented as the hope that the United States can still deliver the American Dream. For example, in the summer of 2016 Michelle Obama delivered a speech at the Democratic National Convention that electrified her audience, as she outlined what she believed to be evidence of American progress. She described how “the generations of people who felt the lash of bondage, the shame of servitude, the sting of segregation . . . kept striving . . . kept hoping so that today I wake up every morning in a house that was built by slaves.”†† Michelle Obama ended her speech declaring triumphantly—in a clear rebuke to Donald Trump—“Don’t let anyone ever tell you that this country isn’t great, that somehow we need to make it great again. Because this right now is the greatest country on earth.” But the actual state of the country has never been measured or determined by the wealthiest and most powerful—even in those few instances when those people are Black or Brown. A more accurate view of the United States comes from the ground, not the perch of the White House. When we judge this country by the life of Charleena Lyles, a thirty-year-old, single Black mother, who was shot seven times and killed by Seattle police officers in June 2017, the picture comes into sharper focus.

The ability to distinguish between the ideology of the American Dream and the experience of the American nightmare requires political a***ysis, history, and often struggle. The Combahee River Collective employed this dynamic approach to politics, not a reductive a***ysis that implied identity alone was enough to overcome the sharp differences imposed by social class in our society. (3/~)

The women of the CRC did not define “identity politics” as exclusionary, whereby only those experiencing a particular oppression could fight against it. Nor did they envision identity politics as a tool to claim the mantle of “most oppressed.” They saw it as an a***ysis that would validate Black women’s experiences while simultaneously creating an opportunity for them to become politically active to fight for the issues most important to them.

To that end, the CRC Statement was clear in its calls for solidarity as the only way for Black women to win their struggles. Solidarity did not mean subsuming your struggles to help someone else; it was intended to strengthen the political commitments from other groups by getting them to recognize how the different struggles were related to each other and connected under capitalism. It called for greater awareness and understanding, not less. The CRC referred to this kind of approach to activism as coalition building, and they saw it as key to winning their struggles. Their a***ysis, “If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression,” captures the dialectic connecting the struggle for Black liberation to the struggle for a liberated United States and, ultimately, the world.

Finally, the CRC was important because of its internationalism. Before the multicultural moniker “women of color,” there were “third world women.” The distinction was important historically as well as politically. It was a way of demonstrating solidarity with women in countries that were often suffering because of the policies and military actions of the US government. It was also a way of identifying with various anticolonial struggles and national liberation movements around the world. But of even more importance was the way that Black women saw themselves not as isolated within the United States but as part of a global movement of Black and Brown people united in struggle against the colonial, imperialist, and capitalist domination of the West, led by the United States. One can see the importance of international solidarity and identification especially today, when the United States so readily uses the abuse of women in other countries, such as Afghanistan, as a pretext for military intervention. (4/~)

The women of Combahee tied their sophisticated political a***ysis to a “clear leap into revolutionary action.” For them, the recognition of oppression was not enough; a***ysis was a guide to action and political activity. This is why this forty-year-old document remains so important. The plight and exploitation of Black women has continued into the twenty-first century, and it is paralleled by growing misery across the United States. The concentration of wealth and power among the “1 percent” is matched only by the growing poverty and deprivation of the bottom 99 percent. Of course, those experiences are not shared equally, as Black women and men are overrepresented in the most dismal categories used to measure the quality of life in the United States. But it does mean that those whom capitalism materially benefits are decidedly small in number, while those with mutual interest in creating a society based on human need are broad and expansive. There are, of course, many obstacles to achieving the kind of consciousness combined with political action necessary to make such a society a possibility. But the CRC Statement offers an a***ysis and a plan for “revolutionary action” that is not limited by time and distance from the circumstances in which the members wrote it. Their anticapitalism, calls for solidarity, and commitment to the radical idea that another world is possible and, indeed, necessary remain relevant. (5/5)

From How We Get Free that I posted a few pages ago.

Mulder

MulderLet's note it was Black feminists that coined the term identity politics: http://historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/combrivercoll.html

- a Black feminist that coined the theory of intersectionality.

Omg really?

Had no idea so f***ing cool

not ezra

not ezrawhy is it always cis white dudes talking about how "identity politics" detract from class discourse? do they not have enough brain elasticity to think about the intersections of class, race and gender at the same time or something? jfc

Most of those cis white dudes, in my experience with the bernie supporting kind, understand just that tho

This sounds like a strawman

Synopsis

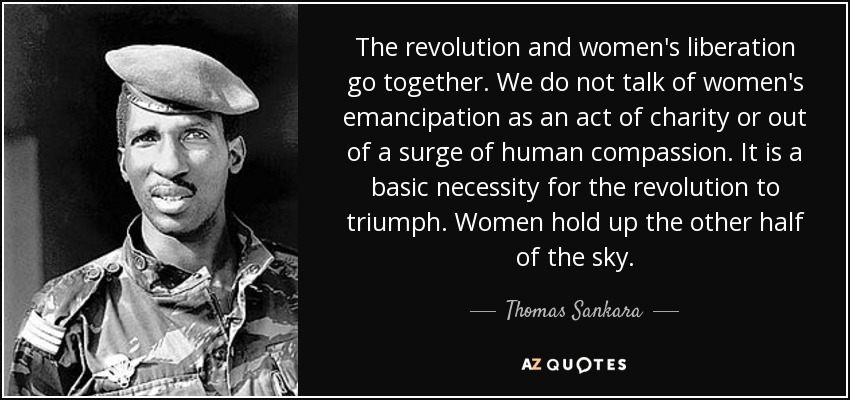

SynopsisThe failure of communist regimes to completely abolish sexism would only mean we need to go even further in our efforts

I think Kate Manne is going to be important in modern feminist theory...

Because she falls into a lot of liberalism (specifically talking about Entitled), and because of this what could be really important a***ysis is weighed down by reformist views.

She also doesn't make clear her definition of terms, and she is hesitant to address Biden and other "left of centre" persons in the chapters.

Sites like The Intercept that present themselves as leftists are defending serial abusers and POS men and there really isn't anybody talking about this either.

Mulder

Mulder@possum

smh...

https://twitter.com/ajplus/status/1294400657655398400She never was the smartest one

Still did a lot of goodA Socialist, Feminist, and Transgender A***ysis of “Sex Work” - Esperanza Fonseca

medium.com/@bfonseca.e/a-socialist-feminist-and-transgender-analysis-of-sex-work-b08aaf1ee4ab

i gotta watch/read some of the content ITT and keep this thread going, maybe in a bit

rnb sponge

rnb spongei gotta watch/read some of the content ITT and keep this thread going, maybe in a bit

rt i haven't posted in a long ass time but i don't want this thread 2 die but this website i s full of guys who resent women adn dont know how to use a stove

i just got my copy of the black maria in the mail bout to start reading it

not ezra

not ezrart i haven't posted in a long ass time but i don't want this thread 2 die but this website i s full of guys who resent women adn dont know how to use a stove

i just got my copy of the black maria in the mail bout to start reading it

so whata means this feminism

not ezra

not ezrart i haven't posted in a long ass time but i don't want this thread 2 die but this website i s full of guys who resent women adn dont know how to use a stove

i just got my copy of the black maria in the mail bout to start reading it

mfs ain’t ever turned the knobs on the stove that’s funny

mfs ain’t ever turned the knobs on the stove that’s funny